As a lad I spent several weeks and weekends each year camping with the Scouts, usually in north Wales, but also in the Lake District, Scotland, and Ireland. It wasn’t very cool compared to other things we did in the 60s, but Baden-Powell established the principles of ‘leave no trace’ so we were ahead of the game as far as today’s Burners and hipsters might be concerned. Admittedly it was so we couldn’t be hunted down by any vengeful Boers rather than from any environmental concerns, but the effect was the same.

I mention this because it meant I had plenty of exposure to vertical, diagonal and horizontal varieties of rain, snow, sleet, fog, and a profusion of wasps, gnats, midges and all the other hazards that nature would conjure up on an hour by hour basis. So when I started to explore the poetry of the Second World War some years later, these experiences made All Day It Has Rained by Alun Lewis (1942) particularly resonant, especially the opening lines.

All Day It Has Rained

All day it has rained, and we on the edge of the moors

Have sprawled in our bell-tents, moody and dull as boors,

And from the first grey wakening we have found

No refuge from the skirmishing fine rain

And the wind that made the canvas heave and flap

And the taught wet guy-ropes ravel out and snap.

But it was the final stanza that aroused my curiosity …

And I can remember nothing dearer or more to my heart

Than the children I watched in the woods on Saturday

Shaking down burning chestnuts for the schoolyard’s merry play,

Or the shaggy patient dog who followed me

By Sheet and Steep and up the wooded scree

To the Shoulder o’ Mutton where Edward Thomas brooded long

On death and beauty – till a bullet stopped his song.

That was the first time I’d encountered the name of Edward Thomas, and it sent me – in the pre-digital age – back to the libraries, the encyclopaedias, and bookshops to find out who this Edward Thomas was and where the Shoulder o’ Mutton might be found. (I discovered it was in Steep, Hampshire, between Reading and Aldershot.)

That was the first time I’d encountered the name of Edward Thomas, and it sent me – in the pre-digital age – back to the libraries, the encyclopaedias, and bookshops to find out who this Edward Thomas was and where the Shoulder o’ Mutton might be found. (I discovered it was in Steep, Hampshire, between Reading and Aldershot.)

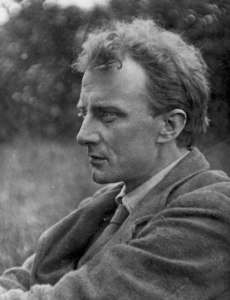

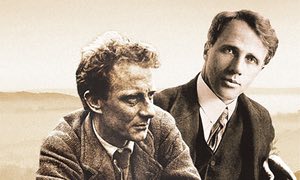

I recalled that poem by Alun Lewis (left) at the beginning of the month when I read of the approaching 100th anniversary of Edward Thomas’s death. Thomas was killed by gunfire at Arras on Easter Monday, 9th April 1917, less than two years after he’d joined the army. As it happens, Lewis also died from a gunshot wound, in Burma in March 1944, less than two years after he’d mentioned Edward Thomas in his earlier poem. In a similarly tragic parallel, in one poem Thomas writes of a soldier killed on his second day in France, and he was killed on the second day of the Battle of Arras.

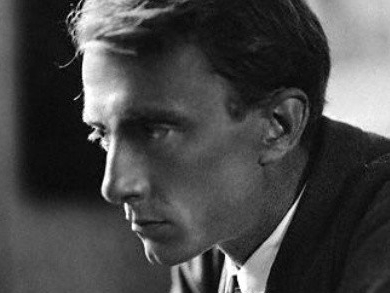

I was attracted to the poets of WW2 because their poems were less about the fighting, and more about the experience of military service and the dislocation from civilian life. Like many people I’d been introduced to the poets of WW1 at school, but in those days the syllabus didn’t go much further than Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. (We couldn’t hang around, there was all this other “literature” to get through.) Isaac Rosenberg and Herbert Read as poets of the First World War probably didn’t make the syllabus because the literary establishment of the 1960s wouldn’t be too keen on promoting the work of Jews or anarchists. Edward Thomas (right) and Rupert Brooke probably weren’t “war-like” enough. The 60s was a great time for presenting the First World War as a carnival of horrors; trench warfare, gas attacks, walking steadily into unwavering machine gun fire, jingoism and unfettered patriotism (in Latin, for effect). Just the thing to animate the imaginations of earnest sixth formers.

I was attracted to the poets of WW2 because their poems were less about the fighting, and more about the experience of military service and the dislocation from civilian life. Like many people I’d been introduced to the poets of WW1 at school, but in those days the syllabus didn’t go much further than Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. (We couldn’t hang around, there was all this other “literature” to get through.) Isaac Rosenberg and Herbert Read as poets of the First World War probably didn’t make the syllabus because the literary establishment of the 1960s wouldn’t be too keen on promoting the work of Jews or anarchists. Edward Thomas (right) and Rupert Brooke probably weren’t “war-like” enough. The 60s was a great time for presenting the First World War as a carnival of horrors; trench warfare, gas attacks, walking steadily into unwavering machine gun fire, jingoism and unfettered patriotism (in Latin, for effect). Just the thing to animate the imaginations of earnest sixth formers.

Edward Thomas in comparison is too subtle. Today, if Thomas’s poetry is known at all, it’s probably for Adlestrop which describes a momentary pause in a journey at the railway station of that name and which is redolent of the Edwardian era that was swept away by the First World War. Thomas only started writing poetry in 1914 after the war had started, but it doesn’t fit with what we might expect of poetry from that time; rather than describing trench warfare, it seeks to capture the timelessness of rural life, the possibilities that every moment offers and the endurance of nature, of people, of sensibility. A poem of Edward Thomas I particularly like is:

As The Team’s Head-Brass

As the team’s head-brass flashed out on the turn

The lovers disappeared into the wood.

I sat among the boughs of the fallen elm

That strewed an angle of the fallow, and

Watched the plough narrowing a yellow square

Of charlock. Every time the horses turned

Instead of treading me down, the ploughman leaned

Upon the handles to say or ask a word,

About the weather, next about the war.

Scraping the share he faced towards the wood,

And screwed along the furrow till the brass flashed

Once more.

The blizzard felled the elm whose crest

I sat in, by a woodpecker’s round hole,

The ploughman said. ‘When will they take it away?’

‘When the war’s over.’ So the talk began—

One minute and an interval of ten,

A minute more and the same interval.

‘Have you been out?’ ‘No.’ ‘And don’t want to, perhaps?’

‘If I could only come back again, I should.

I could spare an arm. I shouldn’t want to lose

A leg. If I should lose my head, why, so,

I should want nothing more. . . . Have many gone

From here?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Many lost?’ ‘Yes, a good few.

Only two teams work on the farm this year.

One of my mates is dead. The second day

In France they killed him. It was back in March,

The very night of the blizzard, too. Now if

He had stayed here we should have moved the tree.’

‘And I should not have sat here. Everything

Would have been different. For it would have been

Another world.’ ‘Ay, and a better, though

If we could see all all might seem good.’ Then

The lovers came out of the wood again:

The horses started and for the last time

I watched the clods crumble and topple over

After the ploughshare and the stumbling team.

‘As The Team’s Head-Brass’, is as powerful as anything written by the more well-known poets of the First World War. There’s even an early statement of chaos theory in there too, with the unforeseen consequences of a lost friend, a fallen tree, the absence of a seat, ‘another world’ not present. Might it also be the last time the lovers come out of the wood again? Might the war claim one of them before the field is ploughed again, before the swords are forged into ploughshares? The iambic pentameter mirrors the rhythm of the horses, the seasons, the country ways. The whole thing just works so well.

By shifting the focus of the war away from the Gothic horror of the battlefield Thomas’s poetry anticipates the poetry of the Second World War which hasn’t enjoyed the same popularity as that written about 1914-18; it was written by a broader spectrum of poets, not just infantry officers, so there is work about the Home Front – the blitz, the munitions factories, the convoys, the land army, as well as the battlefield – and work by women as well as soldiers, sailors, airmen and those in reserved occupations.

Whether we’ve become less shocked by the imagery of horror from a seemingly endless and relentless series of humanitarian atrocities since 1914, or are now as much if not more concerned with aiding survivors of such events rather than just mourning the victims, it’s impossible to say. But Edward Thomas is a man out of his time, with the eye, the subject matter, and sensibility of poets who would follow.

Interest in the life and work of Thomas has increased recently and his work is becoming more widely known. He came to writing poetry towards the end of his life after being encouraged by his friend Robert Frost. Thomas had established a relatively comfortable living as a New Grub Street journalist; he was a prolific reviewer of books, a literary critic and essayist, and spotted the quality of Robert Frost’s first published volume of work. Frost, an American, had come to Britain in 1912 in an attempt to kick-start his  writing career and it was Thomas who provided the initial lift; from this professional encounter a friendship developed. Thomas had a reputation for spotting ‘talent’ and had previously championed Ezra Pound and Walter de la Mare when they were both unknown; further, he was not afraid of chiding established poets when the quality of their work slipped and he criticised Kipling, Thomas Hardy and WB Yeats on different occasions. Frost encouraged Thomas to direct his writing to poetry and after a hesitant start he had a very productive spell of writing in a very short time, although only a handful of his poems were published before his death. Frost had returned to the USA in 1915 and had urged Thomas to join him to write and teach in New England, but after much equivocation, Thomas chose to join the army instead, which – as a 37 year old married man with children – was not expected. It wasn’t that Thomas was unduly jingoistic or had any strong political convictions, but rather he acted on a resolve to demonstrate his willingness to defend and protect the country and people he loved. Rupert Brook may have written if he should die then ‘there’s some corner of a foreign field that is forever England’ but for Thomas that corner would always be a part of every field in England.

writing career and it was Thomas who provided the initial lift; from this professional encounter a friendship developed. Thomas had a reputation for spotting ‘talent’ and had previously championed Ezra Pound and Walter de la Mare when they were both unknown; further, he was not afraid of chiding established poets when the quality of their work slipped and he criticised Kipling, Thomas Hardy and WB Yeats on different occasions. Frost encouraged Thomas to direct his writing to poetry and after a hesitant start he had a very productive spell of writing in a very short time, although only a handful of his poems were published before his death. Frost had returned to the USA in 1915 and had urged Thomas to join him to write and teach in New England, but after much equivocation, Thomas chose to join the army instead, which – as a 37 year old married man with children – was not expected. It wasn’t that Thomas was unduly jingoistic or had any strong political convictions, but rather he acted on a resolve to demonstrate his willingness to defend and protect the country and people he loved. Rupert Brook may have written if he should die then ‘there’s some corner of a foreign field that is forever England’ but for Thomas that corner would always be a part of every field in England.

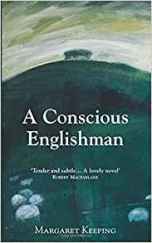

Finally – I’d like to mention a book which looks at the last years of his life, when he was close friends with Frost. Margaret Keeping’s A Conscious Englishman approaches the turmoil in Thomas’s mind from the perspective of his wife, Helen, as revealed  through letters, diaries and articles that survive from that time. Fiction grounded in fact? Creative non-fiction? Take your pick. It’s a good read and worth a tenner of anyone’s money, and presents Thomas as a more grounded, three-dimensional character than you often find in other biographical narratives which just plod through a pre-ordained time table of factual events. I’ve had the pleasure of knowing Margaret for several years and enjoyed discussing the development of this work with mutual friends (you know who you are!) as it was being written. Credit is due also to Frank Egerton and StreetBooks who published the volume. The book is available from Amazon or directly from StreetBooks here (buy).

through letters, diaries and articles that survive from that time. Fiction grounded in fact? Creative non-fiction? Take your pick. It’s a good read and worth a tenner of anyone’s money, and presents Thomas as a more grounded, three-dimensional character than you often find in other biographical narratives which just plod through a pre-ordained time table of factual events. I’ve had the pleasure of knowing Margaret for several years and enjoyed discussing the development of this work with mutual friends (you know who you are!) as it was being written. Credit is due also to Frank Egerton and StreetBooks who published the volume. The book is available from Amazon or directly from StreetBooks here (buy).

Further reading:

Edward Thomas: Collected Poems Faber & Faber, London, 1979.

Hamilton, Ian (ed): The Poetry of War, 1939- 1945 New English Library, London, 1982.

Reilly, Catherine W (ed): Chaos of the Night, Women’s Poetry & Verse of the Second World War Virago, London, 1984.

Skelton, Robin (ed): Poetry of the Forties Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1968.

Very interesting post. Fascinating facts which I did not know.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your interest. Please stop by again.

LikeLike